It was a quiet afternoon in the canteen which had been the case for the last few days, the men joking about the lucky guys who were getting to take a few days off in the infirmary with the “three-day fever.” The afternoon had brought the mail, and my first letter from Papa. I had put it in my uniform pocket, not sure I was ready to read it. It was the first word I had had from him since that cold November afternoon when I had stood in the doorway of the library and said goodbye. Hard to believe that was only two months ago. It seemed years. I had wanted to rush into that room, throw my arms about him, and somehow awaken the affection that must be there between father and daughter. I wanted to take away with me some sign of warmth and caring.

‘Papa, I’m leaving now.”

He had looked up from his manuscript, shielding his eyes from the light of the massive lamp under which he sat, peering at me across the shadows. Except for the raised hand and a slight tremor of the pen in his hand, there was no movement, no invitation.

I waited for a moment and then said softly, “Good-bye Papa.”

Only his lips moved. “You’ve made your bed. Lie in it.”

With a jerk that brought me back to the present I leaned back against the sink and slowly unfolded the letter.

Dear Valerie,

The situation in this country is beyond belief. Any president that gets himself elected on the slogan, “He kept us out of war” and then as soon as he is in office declares one, is an idiot. As you know, I did not vote for him.

You will be glad to know that your brother has won a captaincy. The military as least had the virtue of recognizing ability and breeding and rewarding it. I fail to understand why we have not already licked the Germans.

Of course, we are helping all we can. I have given Emma orders to buy the required amounts of whole wheat, cornmeal and those damnable assorted flours with every sack of white flour. As you know, I detest anything but white. It is also irritating to be short of sugar. Breakfast has ceased to be a pleasure.

I presume by now you are in a position of authority – probably in Paris. If Madame Lagras invites you to her salon, be most circumspect about putting your work in the proper light. You may make it clear to her that I disapprove.

With best wishes for your personal welfare and a speedy end to this ill-advised adventure of yours.

Papa

I folded the letter carefully, pressing each crease, and slipped it back into the envelope. I closed the flap and ran my finger across the return address. Nothing had changed. Why had he even written to me? I folded the envelope in half and then in half again. I shut my eyes tightly for a moment and waited for the wave of hopelessness that swept over me to pass. I would not let his letter affect me the way his presence always had. I was here in a canteen in France thousands of miles from the yellow brick house. I had made it out. I reached up and adjusted my coif, my fingers searching for the Red Cross insignia as if for a talisman.

So, James was a captain. He had never written me about it. In fact, he had never written me anything. The silence made me uneasy. Where was he now? What had he done when he was pulled from his regiment? I found I really could not imagine what he would do.

I looked out at the canteen, still noticeably empty, the few men that were there were quiet, and now there was no joking about the lucky guys in the infirmary. The disease, which we had learned to call the influenza, had begun to grip the base. We heard that one of the repair shops was being converted into an infirmary to take the overflow from the overburdened, small wooden building that housed a doctor and a few beds. Training was grinding to a halt, the constant buzzing of airplane motors suddenly, ominously silent. The only thing that continued regularly was the funerals in the afternoon, although these men had not fallen from the sky, but had died in their beds. One day there were ten caskets on the wagon.

Rosie came in for the afternoon shift, and we sat in the canteen debating about starting the coffee. There was really no point. The few men who could come to the canteen had begun to shun it. It was depressing to come to a place that should be full of people and laughter and find one or two grim souls seated at a table hunched over a cup of coffee.

“I just hate the canteen when it’s empty like this,” said Rosie. “I heard that Gil Harkness got sick today and is in the infirmary. That means we won’t even have the piano.”

“Rosie, that’s awful. Gil’s one of the nicest people here.” And he was. He had kept coming in to play the piano even when there were only a few people in the canteen, and no one had the heart to sing. “I wish there was something we could do. I feel so useless.”

“I just want to stay right here. I don’t want to get near anyone who might give me that horrible disease.” She paused, a distraught look on her face. “Wasn’t it awful when that man collapsed yesterday? I didn’t even want to wipe the table where he had sat.”

Just then Miss Farleigh walked in. Her coif was as crisp as ever, but her blue eyes looked tired, and her spare frame thinner.

“Girls, we need help. The extra doctor and the two nurses they sent down from Paris all got sick last night. I have been in the repair shop all night doing what I could, but there is too much. I am sorry to have to expose you to contagion, but I would like both of you to come with me now.”

“But what about the canteen?” Rosie’s face was as white as her coif. Her voice quavered.

“We’ll just have to shut it down for a while. It isn’t being used very much at the moment.”

“I’ll just run back and get our capes, Miss Farleigh and we’ll be right with you,” I said.

“Wait a minute, Val.” Rosie reached out to stop me, and then faced Miss Farleigh. “Surely this epidemic is getting better. What about the men who will be getting out of the hospital and will want to come to the canteen and relax? There should be someone here to take care of them.” Rosie was leaning forward almost pleading.

Miss Farleigh looked at her appraisingly for a long moment and then said, “Perhaps you are right, Miss Bennet. Perhaps it would be best if you stayed here. Miss Ward get your cape.”

Rosie’s whole body relaxed in obvious relief. “I will be glad to stay. Val you can go to the infirmary. I don’t mind being here alone.”

“I’m sure you don’t.” Miss Farleigh almost bit off her words, but Rosie was too lost in her own relief to notice. “Miss Ward, I’ll meet you out front.”

As I hurried to get my cape, I was glad that Rosie had been allowed to stay at the canteen. And I also understood, much as I admired what Miss Fairleigh had done here in France, that she would make no allowances for any weakness no matter how justified. But I knew what Miss Fairleigh did not. In one of our rare late night conversations Rosie had divulged to me that her mother and a younger sister had died from tuberculosis. She was terrified that would be her fate as well. “The coughing, Val. It just went on and on until they died. Sometimes I would lie in bed at night and cover my ears with my pillow, and then I would feel so bad. I was well and they were sick. But I couldn’t stand it.”

I knew that feeling of helplessness for I had felt it years ago. I could still see Trixie’s small form lying limp and vulnerable in Mamma and Papa’s big bed. It had been an awful evening. The house with its never changing schedule had been thrown awry. The light was still shining down the dining room table long after we had left it. The side lights in the living room had not been lit, and everyone was scurrying around doing things and talking in hushed voices.

I had watched Josie as she had cleared the dining room table, and she had been crying. Dinner had been awful. No one said anything, even Arthur was silent. James had put lumps of butter on his bread without getting a scolding from Papa. I had always dreaded Papa’s criticisms, but tonight any kind of noise would have been welcome. Trixie would have made some kind of noise. Trixie would take the sting out of the worst things said to her older brothers and sister. But it was because of Trixie that the night was awful.

She lay upstairs in Mamma and Papa’s big bed, and she was fighting for her life. Nanny had told me that it was a battle against Death, and I had a very clear picture in my mind of Death wanting Trixie and all of us fighting to keep him away. I was even more worried when Nanny said that “Death was just around the corner.” Although it was way past my bedtime, nobody had given me a thought since dinner. I slipped under the table at the turn in the stairs. Even though I was a big girl for seven, I could sit under the table, and keep an eye on the front door. They could all keep Death out of the bedroom, but I would make sure that he did not get in through the front door. After a few moments I felt very lonely under the table all by myself, and a little afraid of what I would do if Death really did come in the door.

If Death took Trixie, I wanted Death to take me too. Alone without Trixie, way down deep inside I did not know if I could live without Trixie. Would it make a difference to Death if he knew?

I wondered what Death was like. I knew he rode on a white horse and had a face with hollows in both cheeks. But his voice – was it loud or soft? What did he say when he won the battle? What would he say when I told him how I felt about staying with Trixie? He evidently wanted people – as many as he could get – since he went to the trouble of fighting to get them. I would ask him to take me. Just the minute I heard the noise of his coming, I would open the door and speak to him in a loud voice. It would be nice to have some help I thought. James! I would go upstairs and get James and he would help me watch. We both could not fit under the table, James was too big for that, but with him beside me we could sit on the stairs.

I raced for his room and was about to knock when I heard a strange sound coming from inside. I paused, my hand on the doorknob, and then suddenly realized that James was crying. And then I heard the soft voice of Arthur saying soothing things. I had never seen James cry. Boys were never supposed to cry. Neither for that matter were girls – but a boy of eleven. He was crying hard, and I must never let him know that I had heard him crying – crying for Trixie. I would have to go back down the stairs and wait under the table by myself. I crept back to my post.

Suddenly a door opened, and Nanny came out. She did not notice me as she hurried down the stairs. At the end of the hall, she met Josie, and then was joined my Emma and Delia. The four women stood in a close little clump at the far end of the hall, whispering, Emma’s striped kitchen dress stood out against the black uniforms and white aprons of Josie and Delia. But Nanny was the most conspicuous in her black alpaca, and yet she was the smallest and thinnest. After handing Nanny a tray, Josie disappeared down the hall. She had to stay on duty until ten to answer the doorbell in case someone called. Nanny came flying back up the stairs, the tray in her hand. Her eyes had a faraway look. She passed me so quickly that the wind of her passing made a coolness.

My eyelids began to close. I was conscious of being very tired from the inside out. Yet no matter how tired I felt, I must stay and keep watch. I waited and as I did my mind began to slip into the past with Trixie.

“There is a year between you two. Never let anything else get there.” Nanny was saying it to Trixie and me in the severe voice that she used for the most important occasions. We had quarreled – a long time ago when I had been five. I had chosen Yellow Fever as the private disease for my dolls, inspired by the returning soldiers from the Spanish-American War, and had insisted that Trixie have typhus for hers. Trixie wanted yellow fever and the argument had ended in my hurling her suffering dolls across the playroom. Trixie, in tears, appealed to Nanny and the outcome was a long walk in the chill of a November afternoon. Up the boulevard and across the park we had marched, my blue mitten gripped firmly in Nanny’s right hand and Trixie’s red mitten in her left. Three pairs of booted feet tramped in grim unison over a new fall of snow. Up and back, up and back until the winter cold had cooled our tempers. How ashamed I had felt after that walk. Nanny had made us go for discipline, but Trixie alone had been disciplined. The cold, the snow, the walk had not touched my energy. I had felt exhilarated. I had not been punished. But Trixie had – her face drawn and her steps lagging. I had felt no pleasure in seeing my sister defeated. Instead, I had wanted to protect her. After that Trixie’s dolls had yellow fever as often as Trixie pleased. Only the year should be between us.

But there was something between us now, and all I could do was stand guard. It all seemed so hopeless. I put my hands to my face, and they came away damp. Had all that water come from my eyes? I did not even know I was crying.

Someone was pulling at my hands, lifting me to my feet. I raised my head and looked into Nanny’s face. Hand in hand we walked to the nursery. Nanny sat in her old rocker. I was big for seven, but I climbed into her lap and put my head down close where I could hear her heart beating. For a minute the only sound was the thump-thump of her heart, and the funny little rattle of the chair as it rocked. Back and forth, back and forth.

“Poor dearie,” Nanny said. “Everyone forgot you.”

I pressed my lips against the black alpaca so that only the one word could come out. “Trixie?”

“She’s all right.

“Do James and Arthur know?”

“Your father will tell them.”

I sighed, a deep sigh that began at my toes. I felt very heavy. My ear was pressing against Nanny’s heart. I could hear her voice as if it were coming from inside. It was low and clear and full of throbbing. It sounded as if it were talking to itself.

“Some people say that love is everything, but they’re wrong. It takes courage too. It takes courage to go on living. No matter what the world does to you, you can go on.”

Her voice ended. The rocking went on and on. Pressed against Nanny’s heart, my body swaying, my mind at peace, I watched Death, hollow cheeked and pale, ride around the corner on his white horse. It happened to be the corner of forty-seventh and Grove where Barr’s drugstore was, and I could look through the two big windows and see him between the glass windows riding off. Death had lost the battle. Once again only the year stood between Trixie and me. Courage, courage the rockers seemed to say as Nanny rocked on, her arms encircling me.

I had not been able to help then, and I certainly had not helped later when the case had been even more desperate. But Miss Farleigh thought I could be useful now, and I would give it my best. I would do this for Trixie, and perhaps it would alleviate some of my guilt. I wrapped my cape tightly about me and followed her out on the duckboard walk. When it ended, we stepped off into the omnipresent mud, and headed for the repair shop.

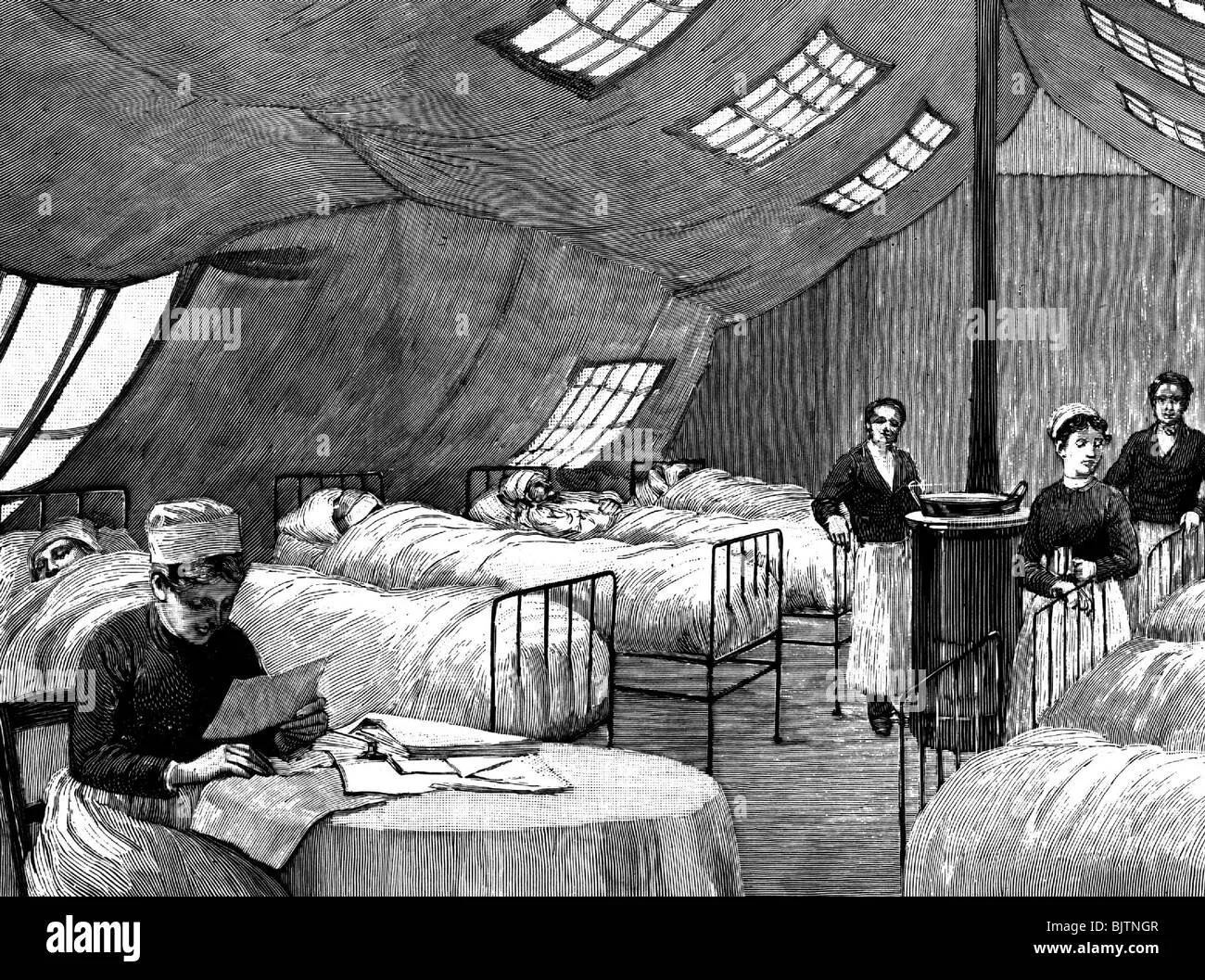

“The worst cases are in the infirmary so the doctor spends most of his time there. All the others are in here,” Miss Farleigh said as she opened a small door and we went in. At first breath, in spite of all my best resolve, I reeled back in horror. It seemed as if I was looking at an ocean of beds, all of them filled. But it was the smell that was overwhelming. The room seemed almost lost in a miasma of unwashed, sweating bodies, urine, and vomit. My stomach rolled and I thought for a moment that I was going to be sick. Then I felt Miss Fairleigh’s hand on my arm.

“Just stand here for a moment, Valerie. You’ll become used to it in a minute.”

Valerie not Miss Winthrop. It was as if I had been admitted to a club – welcomed into the ranks of women like Miss Fairleigh. I had been named for a wealthy, but eccentric maiden aunt in hopes that her worldly good would come my way. To my father’s disappointment, the aunt had given her all her money to an animal rescue organization with the stipulation that they take care of her many cats. But I had always rejoiced in the fact my name meant brave and strong, and now I had a chance to live up to that. I could not fail this indomitable woman.

Yet, at first I was hesitant and embarrassed to approach the beds of men I knew from the canteen. However, the demands of the influenza soon drove all before it. Those who had light cases or who were now recovering wanted me to stop by their beds for a moment just to talk. They would straighten their covers and apologize for their beards and try to keep me nearby as they sipped their water slowly, or asked for their beds to be rearranged.

I spent most of my time, however, with those who were the most ill. There was little I could do besides try to ease the high fevers with cool towels or help feed those who were too weak to feed themselves. I also learned what slop bowls were for, and how to change beds that the men had fouled. I bathed sweat covered bodies and changed damp night shirts. What would have been beyond thinking on Ellis Avenue, was necessary and right here.

Whenever I could stand it no longer, I would creep back to my room behind the canteen and catch a few hours of sleep. I seldom saw Rosie, but assumed that the canteen was keeping her busy. Once when I came back late at night I was surprised to see her still up, but I was too tired to ask why and just fell into bed, going to sleep immediately.

After a week I was asked to help in the infirmary. It was smaller than the repair shop, but every case was critical. The quietness of desperation hung over the room, punctuated only by the labored breathing and cough of the ill. As I entered, the doctor, black circles under his eyes and a stubble on his chin, was pulling a sheet over the face of one of the men. He just nodded to me wearily. In the next bed, eyes closed, a fevered sheen on his face, lay Gil Harkness. As I stood there he suddenly started shaking with chills so violent that the bed trembled. I could hear his teeth chattering from the door. Not Gil. Not if I could help it. He somehow represented what was the best in all of us. From a small town in the Midwest, he had told us all about his four sisters and little brother, and when he sat down at the piano to play it was as if that family circle had widened to include us all.

I went to his bed and wrapped his blankets more tightly around him, willing the warmth of my body into his. It seemed an eternity before the shaking stopped, but slowly his body subsided and as it did, he opened his eyes.

“Val ----what ----shouldn’t be here.”

Then a paroxysm of coughing swallowed his words as I struggled to help him sit up and ease the pain in his chest. The coughing stopped and as I laid him back down he mumbled, “Thanks” and drifted off into a feverish sleep.

“Well done Green Eyes.” The voice came from the back of the room. In surprise I turned around.

“Bazz, are you ------?”

“It’s wonderful to see your concern, but no I’m not. I have just been coming in here to lend the doc a hand. Some of these lads are rather big for you ladies to be lifting.”

“Is this -----why are you here?” I looked into his eyes, his sardonic expression at odds with his actions.

“No, Miss Stickler for Rules. I’m not supposed to be here. I came because I think it’s a good idea. There’s not much action with everyone sick and I was bored. What about you?”

“Miss Farleigh needed help and Rosie agreed to stay and take care of the canteen.”

“An interesting way to phrase it. Yes, little Miss Bennett is certainly enjoying her nobility. While the cat’s away-----“

“Bazz, that’s not-----“

He broke in. “Never mind Val. Just don’t wear yourself out being an angel of mercy.”

“Don’t worry. I never get sick. Nanny used to say I had the constitution of a horse.” I was warmed by his concern, however, and touched but puzzled that he was here.

Gil became a special case for me. So many in this room left only to go to the afternoon funerals. I would make my rounds with an eye on him, and often sit with him for a few moments before going back to my room. Five days after I came to the infirmary, his face lost its fevered glow, and his coughing began to subside. It was as if with the passing of Gil’s crisis, the whole epidemic began to pass too. No new cases were admitted and the room began to empty. The base returned to normal, if on wobbly legs. I could even hear the sound of planes as the men started training once more. It was time for me to get back to the canteen. A long night of uninterrupted sleep would be wonderful. I was so tired I ached from one end to the other. I looked around the almost empty infirmary, and as I reached for my cape I felt suddenly cold. I turned to see who had opened the door, but it was shut. Suddenly my body began to shake with chills, and I had to clamp my jaws tightly together to keep my teeth from chattering. No, it could not be. I never got sick. I was just tired from all the work. My cape felt as if it weighed a hundred pounds. I heard the door open. “Bazz …” I said and then I felt his arms around me and remembered nothing else.

The next few days floated by in alternating heat and cold, and then the coughing began. I felt as if my body would be torn apart. Sometimes I would see Miss Farleigh’s face and sometimes the doctor’s and sometimes Bazz’s. They all seemed to float just above me out of my reach. Then one day I woke up and the room was bright, in focus, and my head was clear. Bazz was sitting in a chair next to my bed, his head on his chest dozing. As I shifted in bed, he woke with a start, and then looked me over appraisingly.

“Welcome back to beautiful Issoudun.” His grin was as sardonic as ever, but his face looked tired, and there were circles under his eyes.

I tried to marshal my thoughts. “What ---- how long----what happened?”

“Well, Val. Just when we thought all the fun was over, you collapsed ever so gracefully in my arms, and proceeded to give us quite a scare.”

“Yes, I --- I think I remember. What are you doing here?”

“Just resting a bit.” He turned in his chair. “Doc, she’s awake.” As the doctor came across the room he turned back to me. “Now that you seem better, I think I will go and get some sleep. I must get back to work sometime you know.” He leaned over and gave me a light brushing kiss on the forehead and was gone.

I made a rapid recovery, but it was quite a few days before I returned to my duties at the canteen. Miss Farleigh welcomed me back with a warm smile and handshake. Rosie greeted me guardedly and turned back quickly to her work.

As I moved among the tables, all the men had a kind word for me. I was warmed by their friendship. They now seemed more my family than the people with whom I shared the same last name. As I passed the piano, Gil struck a couple of chords and announced, “Here’s the lady that saved my life. Glad to have you back, Val.”

Len leaned over and said, “Too bad you couldn’t have improved his playing as well.” It felt good to take part in the general laughter.

The one disappointment of my return was that we still heard the funeral march every day at three. No officer in charge of flying had appeared yet, and once the epidemic was over the flyers had returned to their old ways. Not content to have escaped death on the ground, they went up in the air drunk, tired or untrained and met it there.

With Bazz I felt I had lost something precious. The easy-going intimacy of the infirmary was gone. He did not come to see me while I was convalescing. I had been told that he had been in and out all the time I was delirious and had taken turns with Miss Farleigh watching by my bed in my worst moments. But once I was better, he never returned, although I looked for him. I was back at work two days before he sauntered into the canteen. I was washing one of the huge marmites and immediately wiped my hands and left the kitchen to talk to him.

“Bazz, I’ve been waiting for you to come in.”

He looked at me intently for a moment, then the old sardonic smile was back. “And why would that be?”

“To thank you for all you did for me. Miss Farleigh said that -----“

“Miss Farleigh probably talked too much. I did just what I wanted to do and nothing else.”

“But you worked in the infirmary when you didn’t have to and ------“But I was stopped by the look on his face.

“Listen, Val. Don’t go getting wonderful ideas about me. I don’t live in your rosy, make-believe little world. Hasn’t your bout in the infirmary made you realize how short life is? Too short to live by rules. I worked in the infirmary because I thought it necessary, not because some damn fool ordered me to.” He paused for a moment looking at me appraisingly. “Come with me after taps tonight. To a bon party.”

“You know I can’t do that.”

“You can, but you won’t. There is a difference. Others have discovered that. You could take a lesson or two from -----. Oh, never mind.” He turned away from me towards the piano. Eager faces looked up to greet him as he called, “Hey, let’s get this party started.” He disappeared into the crowd around the piano, and I returned to washing out the marmite fighting disappointment over something I could not quite put my finger on.